Regulation Name: Legal Entities Transparency Act (LETA)

Date Of Effect: 11 Sep 2025

Region: Switzerland

Agency: Swiss Federal Parliament

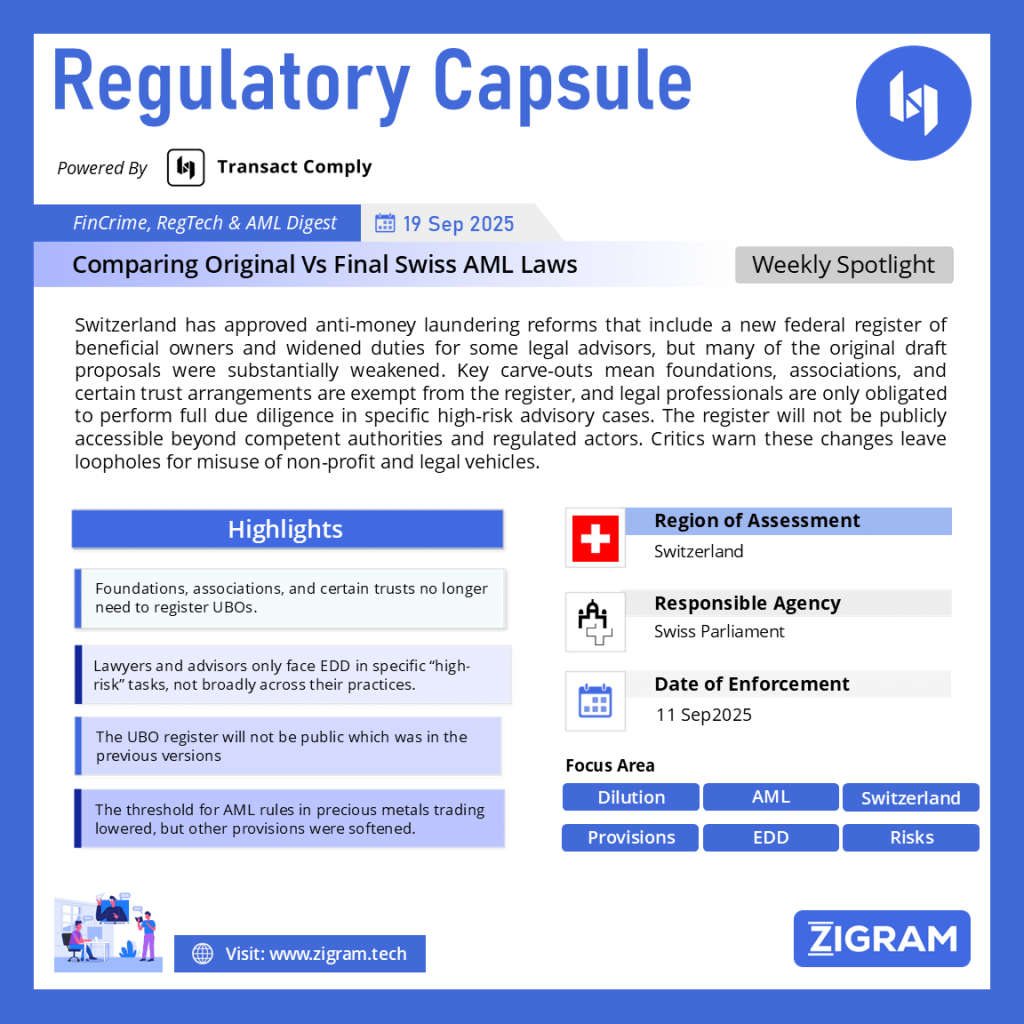

Comparing the original AML reform proposals with the watered-down final package in Switzerland

Switzerland’s 2023–2025 reform process aimed to close longstanding transparency gaps in the fight against money laundering by introducing a federal beneficial-ownership (UBO) register and by expanding due-diligence duties outside traditional banking (notably to some legal and advisory activities). Over the parliamentary process the bill was narrowed: important exemptions were added, the scope of due-diligence for legal professions was curtailed, and certain enforcement proposals were softened. The result is a package that moves Switzerland closer to international standards but falls short of the more comprehensive measures ministers initially proposed. The Federal Council’s dispatch launching the reform is on the government website. (See Federal Council dispatch, May 22, 2024.)

1. Legislative background and where the draft came from

1.1 Why the reform was launched

The Federal Council initiated a formal consultation to strengthen Switzerland’s AML framework because international evaluations and global developments had exposed gaps: trusts, foundations and certain advisory activities were not always transparent to authorities and financial intermediaries. The consultation (launched August 2023) and the Federal Council’s subsequent dispatch (May 2024) proposed a two-track reform: a new federal law to create a central transparency register for legal entities and a partial revision of the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) to extend due-diligence duties and tighten sectoral rules. The Federal Office of Justice was identified to manage the register in the draft. See the consultation and the Federal Council dispatch for official framing.

1.2 Legal instruments involved

The reform involved creating a new federal transparency/UBO law (often referenced as the Legal Entities Transparency Act / “LETA” in commentary) to establish the central register, and a partial revision of the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) to broaden due-diligence coverage and sectoral measures (precious metals, real estate). The standing Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) and FINMA ordinances form the baseline legal framework to which the amendments would attach. Official sources for AMLA and the legal basis are maintained by Fedlex and the State Secretariat for International Finance (SIF).

2. The original proposals — what the government and drafters requested

2.1 The federal UBO / transparency register design in the draft

In the original government proposal the central idea was a federal register that would require Swiss legal entities (and certain foreign entities that have substantial connections to Switzerland) to record their ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs). The register was to be managed centrally (proposed management: Federal Office of Justice), accessible to competent authorities and to financial intermediaries for AML purposes, and protected (i.e., not public in the same way as some international registries). The draft defined UBO thresholds (typically 25% ownership/control) and required entities to identify and update UBO data. See the Federal Council’s dispatch and commentary on the drafting (LETA proposal).

2.2 Due-diligence expansion for legal and advisory professions

The draft sought to extend explicit AML due-diligence obligations to advisors and certain legal professionals when they carried out “high-risk” activities such as company formation and structuring, trust and fiduciary services, and real-estate deals. This would bring many advisory activities that facilitate ownership concealment into the AML perimeter so that client identity, UBOs, and in high-risk cases source-of-fund inquiries would be required. The policy rationale, stated in government material, was to plug the non-financial sector gap and align with FATF expectations. See the consultation papers and legal commentary for details.

2.3 Sectoral tightening and thresholds

The draft proposed lowering cash thresholds for regulated checks (for instance, in precious metals and stones the draft reduced thresholds to CHF 15,000) and made cash payments in real-estate transactions subject to AML checks regardless of amount. It planned to tighten registration and verification obligations across affected sectors, and to bolster supervision and sanctions for non-compliance, including clearer accountability for self-regulatory organisations (SROs). See government dispatch and advisory summaries for the draft technical measures.

3. The parliamentary amendments — how the original proposals were watered down

3.1 The UBO register retained but narrowed: exemptions for foundations, associations and some trusts

Parliament accepted the federal register in principle but introduced carve-outs. Notably, the National Council and Council of States agreed that foundations, associations and certain trustee/trust arrangements would be exempt from the obligation to register their UBOs. The parliamentary intent, evident in the debates and media reporting, was to avoid imposing an onerous burden on civil-society organisations and to preserve specific traditional structures. In practice, this means a class of legal vehicles—some commonly used in wealth planning—remain outside mandatory registry coverage, creating continuing transparency gaps compared with the original draft. Media coverage and legal reporting of parliamentary votes confirm these exemptions.

3.2 Narrower scope for legal professions and advisers: only certain high-risk activities captured

A central watering-down concerned who among lawyers, notaries and other advisers would be brought within AML duties. Rather than a broad, near-universal expansion of due diligence for many advisory activities, Parliament limited the extension to defined, concrete high-risk activities (for example, lawyers advising on company formation or real-estate conveyancing in particular circumstances). The effect is to preserve professional secrecy and ordinary legal representation from automatic inclusion in the AML reporting regime—an outcome that the legal profession and some representatives had pressed for. That narrowing reduces both the number of transactions and types of advisers that must perform full UBO verification under law. Analysis of the parliamentary outcome and commentary from legal associations documents this narrowing.

3.3 “Presumption of correctness” and verification standards weakened in practice

Although entities are required to declare UBOs, parliamentary amendments and the final drafting created conditions where self-declarations could stand without systematic independent verification in all cases. Civil society organisations warned that the combination of exemptions and acceptance of unverified declarations creates a substantive loophole: actors using exempt vehicles or unverified corporate statements may remain unattributable in many investigations. Transparency International publicly cautioned against weakening the verification duty because it would blunt the register’s effectiveness.

3.4 Limited public access and protection of privileged information preserved

From the outset the government proposed a non-public register with access restricted to competent authorities and obliged entities. Parliament retained the guarded approach and reinforced protections for information subject to professional secrecy. That choice means outside investigators, journalists and the wider public will not have the same direct access that some international models allow; instead, access rests on authorised queries by competent authorities and regulated intermediaries. The net effect is a register useful for authorities but limited as a transparency tool for wider civil-society oversight.

3.5 Enforcement and sanctions: some tougher measures stayed, but others were softened or removed

The draft’s more expansive enforcement proposals—particularly those that would have tightened supervisory sanction powers over SROs and created stiffer administrative fines—were scaled back in Parliament. Certain proposed sanctioning mechanisms and accountability measures for some self-regulatory bodies were removed or made less prescriptive. This decreases the immediate legal pressure on weaker compliance regimes and places more emphasis on voluntary compliance and sectoral self-regulation in some areas. Sources reporting these changes reference the Federal Council’s revised messaging and parliamentary decisions.

4. Clause-level detail and where to find the legal text

For readers who want the exact legislative wording, there are two authoritative document families to consult: the Federal Council’s dispatch (which sets out the government’s proposed articles and rationale), and the parliamentary (final) bill texts and votes published on official platforms (Fedlex / Federal Gazette and the parliamentary documentation portal). The present official AML law (AMLA) text is available on Fedlex; the new Transparency Act (LETA) drafts and the parliamentary message and revisions are available via the Federal Chancellery / Federal Council pages and will be consolidated in Fedlex as the law is finalized. The government’s dispatch and the Fedlex AMLA text are the starting points for clause-by-clause comparison.

If you want, I can fetch the current parliamentary bill text (the version approved by the National Council and the Council of States) from Fedlex or the parliamentary records and produce a redline comparison with the government’s original draft showing the precise article/paragraph changes (for example: “LETA Article X, paragraph Y—original required registration of ‘foundations’ but now excludes foundations: see text …”). Tell me if you want the redline vs the official final text and I’ll extract the exact article numbers.

5. Practical implications of the watering-down (what changed in day-to-day compliance)

Because the register is non-public, contains exemptions for foundations/associations/trusts, and because certain legal professions retain privileged status except in clearly defined high-risk activities, several operational realities change for firms and regulators.

First, banks and other financial intermediaries cannot rely solely on the register to prove a complete picture of ownership where exempted entities are involved; they must supplement register data with additional external verification and enhanced due diligence. Second, legal advisers and notaries who do fall within the “high-risk” boxed activities must operationalise client due diligence in those contexts, but many routine legal representation tasks remain outside the AML perimeter—creating complexity in triaging when a transaction is in scope. Third, weaker sanction mechanisms for SROs and the acceptance of self-declarations create an environment where compliance quality will vary by sector and by SRO, requiring firms to treat SRO membership more as a minimum requirement and to build internal controls above regulatory minima. Analysts and law firms explain these compliance consequences in practical guides to the register and the AML revisions. See Grant Thornton and other practitioner guides.

6. Criticism, international reaction and risk to Switzerland’s AML reputation

Civil society organisations, notably Transparency International, have publicly warned that exemptions and watered-down verification duties could severely blunt the reform’s effectiveness, leaving holes through which illicit actors can move funds. International evaluators (e.g., FATF) judge not only the presence of rules but their scope and enforcement. Observers note that while the reforms are a step forward (a national register is better than the status-quo fragmentation), the remaining gaps could be raised in future evaluations and may affect perceptions of Switzerland’s willingness to meet the highest transparency standards. Media reporting and NGO statements document these concerns.

Conclusion — how big a step forward versus how big a compromise

The Swiss legislative process produced a compromise: a federal UBO register and clarified AML in several sectors represent important progress from the prior fragmented situation, but carve-outs for foundations/associations/trusts, the protection of many legal representation activities via professional secrecy, limited public access to the register, and softened enforcement provisions mean the final law is materially less comprehensive than the government’s original proposals.

For regulators and compliance teams the takeaway is pragmatic. The register will provide value for many investigations and due-diligence checks but cannot be treated as a single source of truth—especially where exempt vehicles, trusts or privileged legal activity are involved. Firms should therefore prepare operationally to verify UBOs outside the register, update internal risk frameworks to reflect the residual transparency gaps, and monitor future regulatory guidance and any FATF commentary which may follow.

Sources:

Federal Council dispatch on strengthening AML framework (official)

Federal consultation launch (official)

Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) (Fedlex; baseline legal text)

State Secretariat for International Finance (SIF) — AMLA overview

Swissinfo reporting on the federal UBO register (analysis/press)

Bluewin / press summary of parliamentary decisions (June 2025)

IFCReview / Transparency International coverage and warnings

Grant Thornton practitioner note on transparency register and AML changes

Lenz & Staehelin summary of the LETA proposal and UBO register

IFCReview / IFC reporting on the parliamentary outcomes and register

Practical explainer — My Swiss Company (UBO register overview)

Read about the product: Transact Comply

Empower your organization with ZIGRAM’s integrated RegTech solutions – Book a Demo

- #AMLReform

- #Switzerland

- #Transparency

- #BeneficialOwnership

- #LegalReform

- #FinancialCrime

- #MoneyLaundering

- #UBORegister

- #RegulatoryChange

- #Compliance